The human mind is a complex and fascinating entity that influences our thoughts, emotions, and actions. In the field of psychology, there are various theories and concepts that attempt to explain the workings of the mind. One such theory is Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, which suggests that the mind is composed of three components: the Id, Ego, and Super-ego. These three components are believed to play a significant role in shaping our behavior and decision-making processes. In this essay, we will explore the components of the mind known as Id, Ego, and Super-ego, and discuss how they influence our actions and choices.

Id, ego and super-ego are the three parts of the psychic apparatus defined in Sigmund Freud’s structural model of the psyche; they are the three theoretical constructs in terms of whose activity and interaction mental life is described. According to this model of the psyche, the id is the set of uncoordinated instinctual trends; the ego is the organised, realistic part; and the super-ego plays the critical and moralising role.

Even though the model is “structural” and makes reference to an “apparatus”, the id, ego and super-ego are functions of the mind rather than parts of the brain and do not correspond one-to-one with actual somatic structures of the kind dealt with by neuroscience.

The concepts themselves arose at a late stage in the development of Freud’s thought: the “structural model” (which succeeded his “economic model” and “topographical model”) was first discussed in his 1920 essay “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” and was formalised and elaborated upon three years later in his “The Ego and the Id”. Freud’s proposal was influenced by the ambiguity of the term “unconscious” and its many conflicting uses.

Id

The id comprises the unorganised part of the personality structure that contains the basic drives. The id acts according to the “pleasure principle”, seeking to avoid pain or unpleasure aroused by increases in instinctual tension.

The id is unconscious by definition:

“It is the dark, inaccessible part of our personality, what little we know of it we have learned from our study of the dream-work and of the construction of neurotic symptoms, and most of that is of a negative character and can be described only as a contrast to the ego. We approach the id with analogies: we call it a chaos, a cauldron full of seething excitations… It is filled with energy reaching it from the instincts, but it has no organisation, produces no collective will, but only a striving to bring about the satisfaction of the instinctual needs subject to the observance of the pleasure principle.”

In the id,

“contrary impulses exist side by side, without cancelling each other out….There is nothing in the id that could be compared with negation…nothing in the id which corresponds to the idea of time.”

Developmentally, the id is anterior to the ego; i.e. the psychic apparatus begins, at birth, as an undifferentiated id, part of which then develops into a structured ego. Thus, the id:

“…contains everything that is inherited, that is present at birth, is laid down in the constitution — above all, therefore, the instincts, which originate from the somatic organisation, and which find a first psychical expression here (in the id) in forms unknown to us.”

The mind of a newborn child is regarded as completely “id-ridden”, in the sense that it is a mass of instinctive drives and impulses, and needs immediate satisfaction, a view which equates a newborn child with an id-ridden individual—often humorously—with this analogy: an alimentary tract with no sense of responsibility at either end.

The id is responsible for our basic drives, “knows no judgements of value: no good and evil, no morality…Instinctual cathexes seeking discharge — that, in our view, is all there is in the id.” It is regarded as “the great reservoir of libido”, the instinctive drive to create — the life instincts that are crucial to pleasurable survival. Alongside the life instincts came the death instincts — the death drive which Freud articulated relatively late in his career in “the hypothesis of a death instinct, the task of which is to lead organic life back into the inanimate state.” For Freud, “the death instinct would thus seem to express itself — though probably only in part — as an instinct of destruction directed against the external world and other organisms.”: through aggression. Freud considered that “the id, the whole person…originally includes all the instinctual impulses…the destructive instinct as well.” as Eros or the life instincts.

Ego

The ego acts according to the reality principle; i.e. it seeks to please the id’s drive in realistic ways that will benefit in the long term rather than bringing grief. At the same time, Freud concedes that as the ego “attempts to mediate between id and reality, it is often obliged to cloak the Ucs. [Unconscious] commands of the id with its own Pcs. [Preconscious] rationalizations, to conceal the id’s conflicts with reality, to profess…to be taking notice of reality even when the id has remained rigid and unyielding.”

The ego comprises that organised part of the personality structure that includes defensive, perceptual, intellectual-cognitive, and executive functions. Conscious awareness resides in the ego, although not all of the operations of the ego are conscious. Originally, Freud used the word ego to mean a sense of self, but later revised it to mean a set of psychic functions such as judgment, tolerance, reality testing, control, planning, defence, synthesis of information, intellectual functioning, and memory. The ego separates out what is real. It helps us to organise our thoughts and make sense of them and the world around us.”The ego is that part of the id which has been modified by the direct influence of the external world … The ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions … in its relation to the id it is like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with his own strength, while the ego uses borrowed forces.” Still worse, “it serves three severe masters…the external world, the super-ego and the id.” Its task is to find a balance between primitive drives and reality while satisfying the id and super-ego. Its main concern is with the individual’s safety and allows some of the id’s desires to be expressed, but only when consequences of these actions are marginal. “Thus the ego, driven by the id, confined by the super-ego, repulsed by reality, struggles…[in] bringing about harmony among the forces and influences working in and upon it,” and readily “breaks out in anxiety — realistic anxiety regarding the external world, moral anxiety regarding the super-ego, and neurotic anxiety regarding the strength of the passions in the id.” It has to do its best to suit all three, thus is constantly feeling hemmed by the danger of causing discontent on two other sides. It is said, however, that the ego seems to be more loyal to the id, preferring to gloss over the finer details of reality to minimize conflicts while pretending to have a regard for reality. But the super-ego is constantly watching every one of the ego’s moves and punishes it with feelings of guilt, anxiety, and inferiority.

To overcome this the ego employs defense mechanisms. The defense mechanisms are not done so directly or consciously. They lessen the tension by covering up our impulses that are threatening. Ego defense mechanisms are often used by the ego when id behavior conflicts with reality and either society’s morals, norms, and taboos or the individual’s expectations as a result of the internalisation of these morals, norms, and their taboos.

Denial, displacement, intellectualisation, fantasy, compensation, projection, rationalisation, reaction formation, regression, repression, and sublimation were the defense mechanisms Freud identified. However, his daughter Anna Freud clarified and identified the concepts of undoing, suppression, dissociation, idealisation, identification, introjection, inversion, somatisation, splitting, and substitution.

“The ego is not sharply separated from the id; its lower portion merges into it… But the repressed merges into the id as well, and is merely a part of it. The repressed is only cut off sharply from the ego by the resistances of repression; it can communicate with the ego through the id.” (Sigmund Freud, 1923)

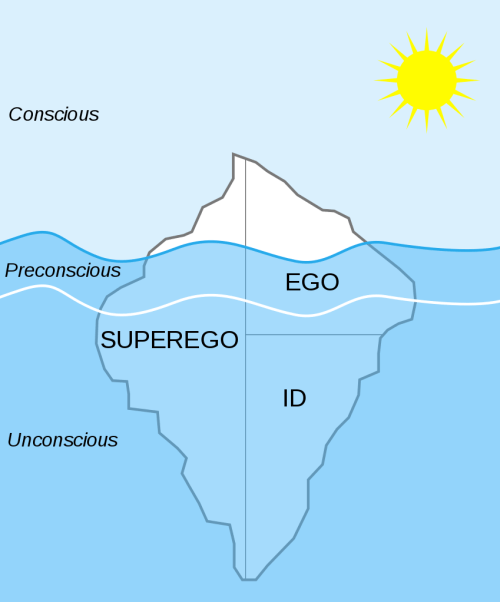

In a diagram of the Structural and Topographical Models of Mind, the ego is depicted to be half in the consciousness, while a quarter is in the preconscious and the other quarter lies in the unconscious.

In modern English, ego has many meanings. It could mean one’s self-esteem, an inflated sense of self-worth, or in philosophical terms, one’s self. Ego development is known as the development of multiple processes, cognitive function, defenses, and interpersonal skills or to early adolescence when ego processes are emerged.

Super-ego

Freud developed his concept of the super-ego from an earlier combination of the ego ideal and the “special psychical agency which performs the task of seeing that narcissistic satisfaction from the ego ideal is ensured…what we call our ‘conscience’.” For him “the installation of the super-ego can be described as a successful instance of identification with the parental agency,” while as development proceeds “the super-ego also takes on the influence of those who have stepped into the place of parents — educators, teachers, people chosen as ideal models.”

The super-ego aims for perfection. It comprises that organised part of the personality structure, mainly but not entirely unconscious, that includes the individual’s ego ideals, spiritual goals, and the psychic agency (commonly called “conscience”) that criticises and prohibits his or her drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions. “The Super-ego can be thought of as a type of conscience that punishes misbehavior with feelings of guilt. For example, for having extra-marital affairs.”

The super-ego works in contradiction to the id. The super-ego strives to act in a socially appropriate manner, whereas the id just wants instant self-gratification. The super-ego controls our sense of right and wrong and guilt. It helps us fit into society by getting us to act in socially acceptable ways.

The super-ego’s demands oppose the id’s, so the ego has a hard time in reconciling the two.

Freud’s theory implies that the super-ego is a symbolic internalisation of the father figure and cultural regulations. The super-ego tends to stand in opposition to the desires of the id because of their conflicting objectives, and its aggressiveness towards the ego. The super-ego acts as the conscience, maintaining our sense of morality and proscription from taboos. The super-ego and the ego are the product of two key factors: the state of helplessness of the child and the Oedipus complex. Its formation takes place during the dissolution of the Oedipus complex and is formed by an identification with and internalisation of the father figure after the little boy cannot successfully hold the mother as a love-object out of fear of castration.

“The super-ego retains the character of the father, while the more powerful the Oedipus complex was and the more rapidly it succumbed to repression (under the influence of authority, religious teaching, schooling and reading), the stricter will be the domination of the super-ego over the ego later on—in the form of conscience or perhaps of an unconscious sense of guilt.”

—Freud, The Ego and the Id (1923)

The concept of super-ego and the Oedipus complex is subject to criticism for its perceived sexism. Women, who are considered to be already castrated, do not identify with the father, and therefore, for Freud, “their super-ego is never so inexorable, so impersonal, so independent of its emotional origins as we require it to be in men…they are often more influenced in their judgements by feelings of affection or hostility.” He went on however to modify his position to the effect “that the majority of men are also far behind the masculine ideal and that all human individuals, as a result of their bisexual disposition and of cross-inheritance, combine in themselves both masculine and feminine characteristics.”

In Sigmund Freud’s work Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) he also discusses the concept of a “cultural super-ego”. Freud suggested that the demands of the super-ego “coincide with the precepts of the prevailing cultural super-ego. At this point the two processes, that of the cultural development of the group and that of the cultural development of the individual, are, as it were, always interlocked.” Ethics are a central element in the demands of the cultural super-ego, but Freud (as analytic moralist) protested against what he called “the unpsychological proceedings of the cultural super-ego…the ethical demands of the cultural super-ego. It does not trouble itself enough about the facts of the mental constitution of human beings.”

Advantages of the structural model

The iceberg metaphor is often used to explain the psyche’s parts in relation to one another.

Freud’s earlier, topographical model of the mind had divided the mind into the three elements of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious. At its heart was “the dialectic of unconscious traumatic memory versus consciousness…which soon became a conflict between System Ucs versus System Cs.” With what Freud called the “disagreeable discovery that on the one hand (super-)ego and conscious and on the other hand repressed and unconscious are far from coinciding,” Freud took the step in the structural model to “no longer use the term ‘unconscious’ in the systematic sense,” and to rename “the mental region that is foreign to the ego…[and] in future call it the ‘id’.” The partition of the psyche defined in the structural model is thus one that cuts across the topographical model’s partition of “conscious vs. unconscious”.

“The new terminology which he introduced has a highly clarifying effect and so made further clinical advances possible.” Its value lies in the increased degree of precision and diversification made possible: Although the id is unconscious by definition, the ego and the super-ego are both partly conscious and partly unconscious. What is more, with this new model Freud achieved a more systematic classification of mental disorder than had been available previously:

“Transference neuroses correspond to a conflict between the ego and the id; narcissistic neuroses, to a conflict between the ego and the superego; and psychoses, to one between the ego and the external world.”

—Freud, Neurosis and Psychosis (1923)

It is important to realise however “the three newly presented entities, the id, the ego and the superego, all had lengthy past histories (two of them under other names)” — the id as the systematic unconscious, the super-ego as conscience/ego ideal. Equally, Freud never abandoned the topographical division of conscious, preconscious, and unconscious, though as he noted ruefully “the three qualities of consciousness and the three provinces of the mental apparatus do not fall together into three peaceful couples…we had no right to expect any such smooth arrangement.”