Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD) is a complex neurological condition that affects how the brain processes and responds to sensory information from the environment. It is a relatively new diagnosis and is often misunderstood, leading to challenges in recognizing and addressing the needs of those affected by it. Individuals with SPD may experience difficulties in processing and regulating various sensory inputs such as touch, sound, taste, and movement. As a result, they may have challenges in daily activities, social interactions, and learning. In this essay, we will explore the specific nature and impact of Sensory Processing Disorder on individuals, including its symptoms, causes, and potential treatments. By understanding this condition, we can better support and advocate for individuals with SPD and help them thrive in their daily lives.

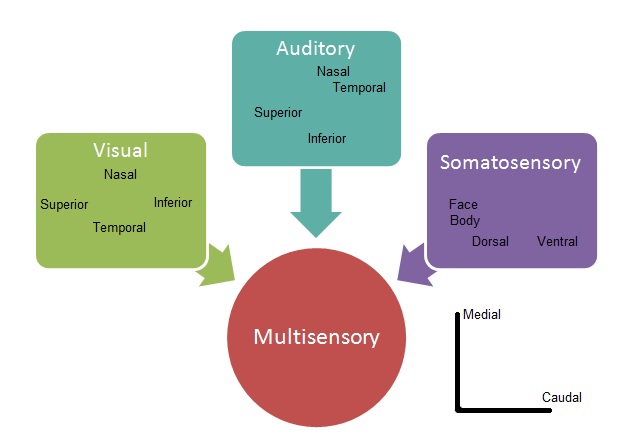

Example of how visual, auditory and somatosensory information merge into multisensory integration representation in the superior colliculus

Sensory processing disorder (SPD; also known as sensory integration dysfunction) is a condition that exists when multisensory integration is not adequately processed in order to provide appropriate responses to the demands of the environment.

The senses provide information from various modalities—vision, audition, tactile, olfactory, taste, proprioception, and vestibular system—that humans need to function. Sensory processing disorder is characterized by significant problems in organizing sensation coming from the body and the environment and is manifested by difficulties in the performance in one or more of the main areas of life: productivity, leisure and play or activities of daily living. Different people experience a wide range of difficulties when processing input coming from a variety of senses, particularly tactile (e.g., finding fabrics itchy and hard to wear while others do not), vestibular (e.g., experiencing motion sickness while riding a car) and proprioceptive (having difficulty grading the force to hold a pen in order to write).

Sensory integration was defined by occupational therapist Anna Jean Ayres in 1972 as “the neurological process that organizes sensation from one’s own body and from the environment and makes it possible to use the body effectively within the environment”. Sensory processing disorder is gaining recognition, although it is still not recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Despite its proponents, it is not widely recognized as a diagnosis by healthcare practitioners.

Classification

Sensory processing disorders are classified into three categories: sensory modulation disorder, sensory-based motor disorders and sensory discrimination disorders (as defined in the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders in Infancy and Early Childhood).

Sensory modulation disorder (SMD)

Sensory modulation refers to a complex central nervous system process by which neural messages that convey information about the intensity, frequency, duration, complexity, and novelty of sensory stimuli are adjusted. Those with SMD present difficulties processing the degree of intensity, duration, frequency, etc., of information and may exhibit behaviors with a fearful or anxious pattern, negative or stubborn behaviors, self-absorbed behaviors that are difficult to engage, or creative or actively seeking sensation.

SMD consists of three subtypes:

- Sensory over-responsivity.

- Sensory under-responsivity

- Sensory craving/seeking.

Sensory-based motor disorder (SBMD)

Sensory-based motor disorder shows motor output that is disorganized as a result of incorrect processing of sensory information affecting postural control challenges, resulting in postural disorder, or developmental coordination disorder.

The SBMD subtypes are:

- Dyspraxia

- Postural disorder

Sensory discrimination disorder (SDD)

Sensory discrimination disorder involves the incorrect processing of sensory information. Incorrect processing of visual or auditory input, for example, may be seen in inattentiveness, disorganization, and poor school performance.

The SDD subtypes are:

1. Visual (sight)

- Eyes are used to distinguish colors, light, shape, and size

2. Auditory (sound)

- Ears are used to perceive sounds

3. Tactile (touch)

- Skin receptors are used to discern shape, size, texture, temperature

4. Gustatory (taste)

- Tongue is used to determine texture and flavor

5. Olfactory (smell)

- Nose is used to interpret odors

6. Vestibular (balance)

- Inner ear is used to determine body’s position in relation to gravity and the ground

7. Proprioception

- Receptors in the muscles and joints are used to determine where parts of the body are located in space

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may vary according to the disorder’s type and subtype present. SPD can affect one sense or multiple senses. While many people can present one or two symptoms, sensory processing disorder has to have a clear functional impact on the person’s life.

Signs of over-responsivity

- Dislike of textures such as those found in fabrics, foods, grooming products or other materials found in daily living, to which most people would not react.

- Avoiding crowds and noisy places

- Motion sickness without medical cause

- Refusal of kissing, cuddling or hugging due to negative experience of touch sensation (not to be confused with shyness or social difficulties)

- Serious discomfort, sickness or threat induced by normal sounds, lights, movements, smells, tastes, or even inner sensations such as heartbeat.

- Picky eating

- Sleep disorders (waking up by minor sounds, problems getting to sleep because of sensory overload)

- Difficulty with calming self, feeling constantly under stress

Signs of under-responsivity

- Difficulty waking up

- Sluggishness and lack of responsiveness

- Lack of awareness of pain or other people

- Apparent deafness even when auditory function have been tested

- Difficulty with toilet training, lack of awareness of being wet or soiled

Sensory craving

- Fidgeting

- Seeking or making loud, disturbing noises

- Climbing, jumping, and crashing

- Seeking “extreme” sensations

- Sucking or biting fingers, clothing, pencils, etc.

- Impulsiveness

Sensorimotor-based problems

- Slow and uncoordinated movements

- Poor handwriting

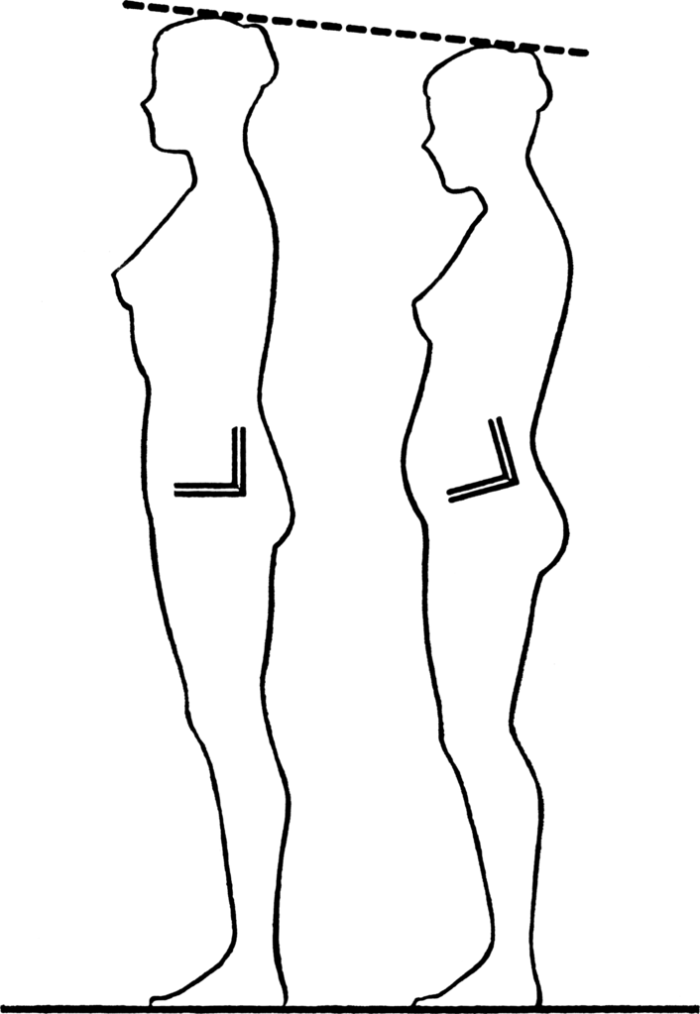

- Poor posture

- Delays in crawling, standing, walking or running.

- Verbosity in order to avoid motor tasks

Poor posture with Anterior pelvic tilt

Sensory discrimination problems

- Things constantly dropped

- Difficulty dressing and eating

- Inappropriate force used to handle objects

Other signs and symptoms

- Poorly integrated balance and rightening reflexes

- Low muscle tone patterns in extensor versus gravity and flexor versus gravity muscle systems

- Poor core tone

- Low postural control

- Poor nystagmus

- Presence of non integrated reflexes such as ATNR

- Jerky eye tracking

- Poor tactile astereognosis

- Inadequate motor, ideational or constructional praxis

- Difficulties with planning movement using feedback information

- Difficulties with planning movement using feedforward information

Causes

The mid-brain and brain stem regions of the central nervous system are early centers in the processing pathway for multisensory integration, these brain regions are involved in processes including coordination, attention, arousal, and autonomic function. After sensory information passes through these centers, it is then routed to brain regions responsible for emotions, memory, and higher level cognitive functions. Sensory processing disorder not only affects interpretation and reaction to stimuli at the midbrain areas, but impacts several higher functions. Damage in any part of the brain involved in multisensory processing can cause difficulties to adequately process stimuli in a functional way.

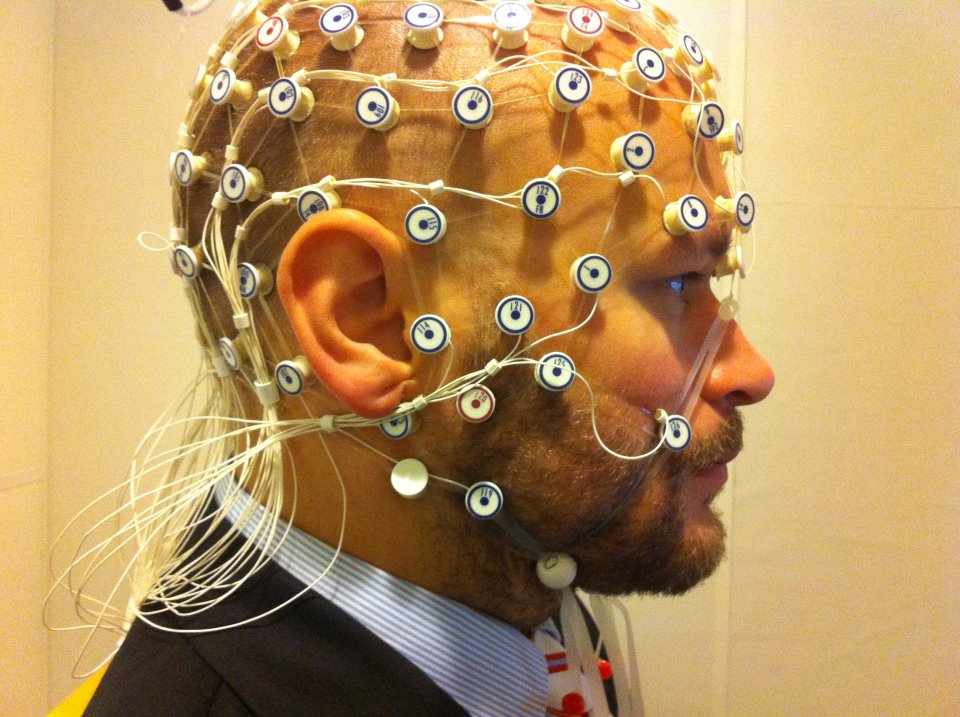

EEG recording

Current research in sensory processing is focused on finding the genetic and neurological causes of SPD. EEG and measuring event-related potential (ERP) are traditionally used to explore the causes behind the behaviors observed in SPD. Some of the proposed underlying causes by current research are:

- Differences in tactile and auditory over responsivity show moderate genetic influences, with tactile over responsivity demonstrating greater heritability. Bivariate genetic analysis suggested different genetic factors for individual differences in auditory and tactile SOR.

- People with Sensory Processing Deficits have less sensory gating (electrophysiology) than typical subjects.

- People with sensory over-responsivity might have increased D2 receptor in the striatum, related to aversion to tactile stimuli and reduced habituation. In animal models, prenatal stress significantly increased tactile avoidance.

- Studies using event-related potentials (ERPs) in children with the sensory over responsivity subtype found atypical neural integration of sensory input. Different neural generators could be activated at an earlier stage of sensory information processing in people with SOR than in typically developing individuals. The automatic association of causally related sensory inputs that occurs at this early sensory-perceptual stage may not function properly in children with SOR. One hypothesis is that multisensory stimulation may activate a higher-level system in frontal cortex that involves attention and cognitive processing, rather than the automatic integration of multisensory stimuli observed in typically developing adults in auditory cortex.

- Recent research found an abnormal white matter microstructure in children with SPD, compared with typical children and those with other developmental disorders such as autism and ADHD.

Research

Diagnosis

Sensory processing disorder since 1994 is accepted in the Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood (DC:0-3R) and is not recognized as a mental disorder in medical manuals such as the ICD-10 or the DSM-5.

Diagnosis is primarily arrived at by the use of standardized tests, standardized questionnaires, expert observational scales, and free play observation at an occupational therapy gym. Observation of functional activities might be carried at school and home as well. Some scales that are not exclusively used in SPD evaluations are used to measure visual perception, function, neurology and motor skills.

Depending on the country, diagnosis is made by different professionals, such as occupational therapists, psychologists, learning specialists, physiotherapists and/or speech and language therapists. In some countries it is recommended to have a full psychological and neurological evaluation if symptoms are too severe.

Standardized tests

- Indicators of Developmental Risk Signals (INDIPCD-R)

- Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT)

- DeGangi-Berk Test of Sensory Integration (TSI)

- Test of Sensory Functions in Infants (TSFI)

Standardized questionnaires

- Sensory Profile, (SP)

- Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile

- Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile

- Sensory Profile School Companion

- Sensory Processing Measure (SPM)

- Sensory Processing Measure Preeschool (SPM-P)

Other tests

- Clinical Observations of Motor and Postural Skills (COMPS)

- Developmental Test of Visual Perception: Second Edition (DTVP-2)

- Beery–Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration, 6th Edition (BEERY VMI)

- Miller Function & Participation Scales

- Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2)

- Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF)

Treatment

Several therapies have been developed to treat SPD.

Sensory integration therapy

Vestibular system is stimulated through hanging equipment such as tire swings

The main form of sensory integration therapy is a type of occupational therapy that places a child in a room specifically designed to stimulate and challenge all of the senses.

During the session, the therapist works closely with the child to provide a level of sensory stimulation that the child can cope with, and encourage movement within the room. Sensory integration therapy is driven by four main principles:

- Just right challenge (the child must be able to successfully meet the challenges that are presented through playful activities)

- Adaptive response (the child adapts his behavior with new and useful strategies in response to the challenges presented)

- Active engagement (the child will want to participate because the activities are fun)

- Child directed (the child’s preferences are used to initiate therapeutic experiences within the session)

Sensory processing therapy

This therapy retains all of the above-mentioned four principles and adds:

- Intensity (person attends therapy daily for a prolonged period of time)

- Developmental approach (therapist adapts to the developmental age of the person, against actual age)

- Test-retest systematic evaluation (all clients are evaluated before and after)

- Process driven vs. activity driven (therapist focuses on the “Just right” emotional connection and the process that reinforces the relationship)

- Parent education (parent education sessions are scheduled into the therapy process)

- “joie de vivre” (happiness of life is therapy’s main goal, attained through social participation, self-regulation, and self-esteem)

- Combination of best practice interventions (is often accompanied by integrated listening system therapy, floor time, and electronic media such as Xbox Kinect, Nintendo Wii, Makoto II machine training and others)

Other methods

Some of these treatments (for example, sensorimotor handling) have a questionable rationale and no empirical evidence. Other treatments (for example, prism lenses, physical exercise, and auditory integration training) have had studies with small positive outcomes, but few conclusions can be made about them due to methodological problems with the studies. Although replicable treatments have been described and valid outcome measures are known, gaps exist in knowledge related to sensory integration dysfunction and therapy. Empirical support is limited, therefore systematic evaluation is needed if these interventions are used.

Children with hypo-reactivity may be exposed to strong sensations such as stroking with a brush, vibrations or rubbing. Play may involve a range of materials to stimulate the senses such as play dough or finger painting.

Children with hyper-reactivity may be exposed to peaceful activities including quiet music and gentle rocking in a softly lit room. Treats and rewards may be used to encourage children to tolerate activities they would normally avoid.

While occupational therapists using a sensory integration frame of reference work on increasing a child’s ability to adequately process sensory input, other OTs may focus on environmental accommodations that parents and school staff can use to enhance the child’s function at home, school, and in the community. These may include selecting soft, tag-free clothing, avoiding fluorescent lighting, and providing ear plugs for “emergency” use (such as for fire drills).

Adults

There is a growing evidence base that points to and supports the notion that adults also show signs of sensory processing difficulties. In the United Kingdom early research and improved clinical outcomes for clients assessed as having sensory processing difficulties is indicating that the therapy may be an appropriate treatment. The adult clients show a range of presentations including autism and Asperger’s syndrome, as well as developmental coordination disorder and some mental health difficulties. Therapists suggest that these presentations may arise from the difficulties adults with sensory processing difficulties encounter trying to negotiate the challenges and demands of engaging in everyday life. It is important when treating adults not only to focus upon sensory regulation but to also help them develop and maintain social supports. Adults who are sensory over-responsive have very high correlated anxiety and depression levels compared to adults who do not have sensory over-responsiveness. This is correlated to the perceived absence of social supporters. Sensory processing disorder can also be correlated with sleep quality in adults. This correlation can be seen especially in adults who have low neurological thresholds (sensory sensitivity and sensory avoidance). These individuals are more sensitive to tactile, auditory and visual stimuli which often impacts their quality of sleep.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that up to 16.5% of elementary school aged children present elevated SOR behaviors in the tactile or auditory modalities. However, this figure might represent an underestimation of Sensory Over Responsivity prevalence, since this study did not include children with developmental disorders or those delivered preterm, who are more likely to present it.

This figure is, nonetheless, larger than what previous studies with smaller samples had shown: an estimate of 5–13% of elementary school aged children. Incidence for the remaining subtypes is currently unknown.

Relationship to other disorders

Because comorbid conditions are common with sensory integration issues, a person may have other conditions as well. People who receive the diagnosis of sensory processing disorder may also have signs of anxiety problems, ADHD, food intolerances, behavioral disorders and other disorders.

Autistic spectrum disorders and difficulties of sensory processing

Sensory processing disorder is a common comorbidity with autism spectrum disorders and is now included as part of the symptomatology in the DSMV.

The abnormally high synchrony between the sensory cortices involved in perception and subcortical regions relaying information from the sensory organs to the cortex is pointed as having a central role in the hypersensitivity and other sensory symptoms that define autism spectrum disorder. Sensory modulation has been the main subtype studied. Differences are greater for under-responsivity (for example, walking into things) than for over-responsivity (for example, distress from loud noises) or for sensory seeking (for example, rhythmic movements). The responses may be more common in children: a pair of studies found that autistic children had impaired tactile perception while autistic adults did not.

The Sensory Experiences Questionnaire has been developed to help identify the sensory processing patterns of children who may have autism.

ADHD

It is speculated that SPD may be a misdiagnosis for persons with attention problems. For example, a student who fails to repeat what has been said in class (due to boredom or distraction) might be referred for evaluation for sensory integration dysfunction. The student might then be evaluated by an occupational therapist to determine why they are having difficulty focusing and attending, and perhaps also evaluated by an audiologist or a speech-language pathologist for auditory processing issues or language processing issues. Similarly, a child may be mistakenly labeled “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)” because impulsivity has been observed, when actually this impulsivity is limited to sensory seeking or avoiding. A child might regularly jump out of their seat in class despite multiple warnings and threats because their poor proprioception (body awareness) causes them to fall out of their seat, and their anxiety over this potential problem causes them to avoid sitting whenever possible. If the same child is able to remain seated after being given an inflatable bumpy cushion to sit on (which gives them more sensory input), or, is able to remain seated at home or in a particular classroom but not in their main classroom, it is a sign that more evaluation is needed to determine the cause of their impulsivity.

Other comorbidities

Various conditions can involve SPD, such as obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency, primary nocturnal enuresis, prenatal alcohol exposure, learning difficulties and people with traumatic brain injury or who have had cochlear implants placed. and may have genetic conditions such as fragile X syndrome.

Controversy

There are concerns regarding the validity of the diagnosis. SPD is not included in the DSM-5 or ICD-10, the most widely used diagnostic sources in healthcare. The American Academy of Pediatrics states that there is no universally accepted framework for diagnosis and recommends caution against using any “sensory” type therapies unless as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan.

Manuals

SPD is in Stanley Greenspan’s Diagnostic Manual for Infancy and Early Childhood and as Regulation Disorders of Sensory Processing part of The Zero to Three’s Diagnostic Classification. but is not recognized in the manuals ICD-10 or in the recently updated DSM-5. However, unusual reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects is included as a possible but not necessary criterion for the diagnosis of autism.

Misdiagnosis

Some state that sensory processing disorder is a distinct diagnosis, while others argue that differences in sensory responsiveness are features of other diagnoses and it is not a standalone diagnosis. The neuroscientist David Eagleman has proposed that SPD may be a form of synesthesia, a perceptual condition in which the senses are blended. Specifically, Eagleman suggests that instead of a sensory input “connecting to [a person’s] color area [in the brain], it’s connecting to an area involving pain or aversion or nausea”.

Researchers have described a treatable inherited sensory overstimulation disorder that meets diagnostic criteria for both attention deficit disorder and sensory integration dysfunction.

Research

Over 130 articles on sensory integration have been published in peer-reviewed (mostly occupational therapy) journals. The difficulties of designing double-blind research studies of sensory integration dysfunction have been addressed by Temple Grandin and others.

History

Sensory processing disorders were first described in-depth by occupational therapist Anna Jean Ayres (1920–1989). According to Ayres’s writings, an individual with SPD would have a decreased ability to organize sensory information as it comes in through the senses.

Original model

Ayres’s theoretical framework for what she called Sensory integration was developed after six factor analytic studies of populations of children with learning disabilities, perceptual motor disabilities and normal developing children. Ayres created the following nosology based on the patterns that appeared on her factor analysis:

- Dyspraxia: poor motor planning (more related to the vestibular system and proprioception)

- Poor bilateral integration: inadequate use of both sides of the body simultaneously

- Tactile defensiveness: negative reaction to tactile stimuli

- Visual perceptual deficits: poor form and space perception and visual motor functions

- Somatodyspraxia: poor motor planning (related to poor information coming from the tactile and proprioceptive systems)

- Auditory-language problems

Both visual perceptual and auditory language deficits were thought to possess a strong cognitive component and a weak relationship to underlying sensory processing deficits, so they are not considered central deficits in many models of sensory processing.

In 1998, Mulligan performed a study on 10,000 sets of data, each representing an individual child. She performed confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses and found similar patterns of deficits with her data as Ayres did.

Quadrant model

Dunn’s nosology uses two criteria: response type (passive vs active) and sensory threshold to the stimuli (low or high) creating 4 subtypes or quadrants:

- High neurological thresholds

- Low registration: high threshold with passive response. Individuals who do not pick up on sensations and therefore partake in passive behavior.

- Sensation seeking: high threshold and active response. Those who actively seek out a rich sensory filled environment.

- Low neurological threshold

- Sensitivity to stimuli: low threshold with passive response. Individuals who become distracted and uncomfortable when exposed to sensation but do not actively limit or avoid exposure to the sensation.

- Sensation avoiding: low threshold and active response. Individuals actively limit their exposure to sensations and are therefore high self regulators.

Sensory processing model

In Miller’s nosology “sensory integration dysfunction” was renamed into “Sensory processing disorder” to facilitate coordinated research work with other fields such as neurology since “the use of the term sensory integration often applies to a neurophysiologic cellular process rather than a behavioral response to sensory input as connoted by Ayres.” The current nosology of sensory processing disorders was developed by Miller, based on neurological underlying principles.

Other models

A wide variety of approaches have incorporated sensation in order to influence learning and behavior.

- The Alert Program for Self-Regulation is a complementary approach that encourages cognitive awareness of alertness often with the use of sensory strategies to support learning and behavior.

- Other approaches primarily use passive sensory experiences or sensory stimulation based on specific protocols, such as the Wilbarger Approach and the Vestibular-Oculomotor Protocol.

Advocacy

The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) supports the use of a variety of methods of sensory integration for those with sensory processing disorder. The organization has supported the need for further research to increase insurance coverage for related therapies. They have also made efforts to educate the public about sensory integration therapy. The AOTA’s practice guidelines currently support the use of sensory integration therapy and interprofessional education and collaboration in order to optimize treatment for those with sensory processing disorder. The AOTA provides several resources pertaining to sensory integration therapy, some of which includes a fact sheet, new research, and continuing education opportunities.